Mc Eschers Impact on Art What Did Mc Ehser Change About Art

MC Escher: An enigma behind an illusion

(Paradigm credit:

2015 The K.C. Escher Company – Baarn, The Netherlands

)

It'south an artwork that has been reproduced endless times in popular culture. Just behind the familiar moving-picture show is a mysterious figure. Alastair Sooke goes in search of MC Escher.

I

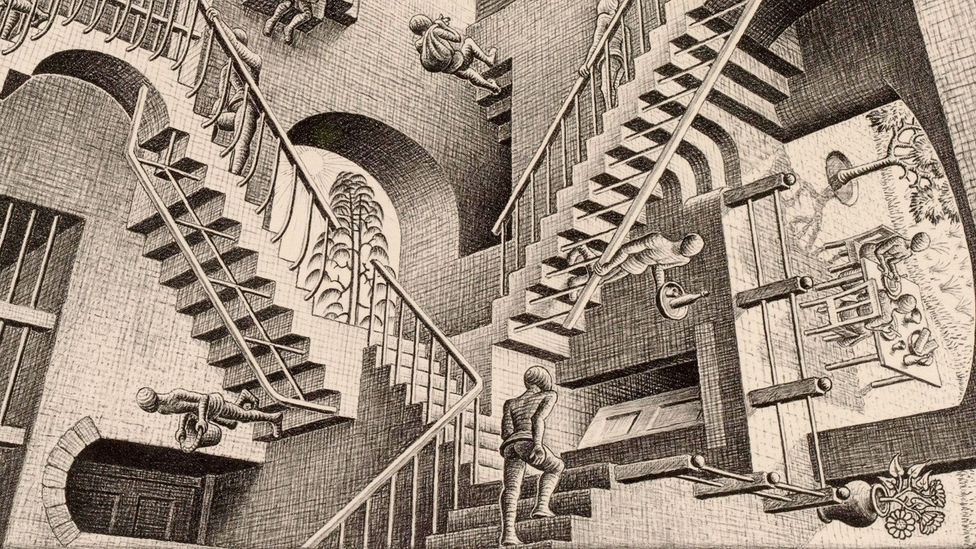

It must be one of the nearly familiar images in mod art: a space-distorting interior that could never exist in reality, dominated past staircases sprouting surreally in all directions, and filled with expressionless, mannequin-like figures walking up and down like members of a religious order calmly going nigh their daily business concern.

Since the original lithograph was produced in the summer of 1953, Relativity – which belongs to a series of five prints by the same artist too featuring incommunicable constructions and multiple vanishing points – has been reproduced countless times on posters, mugs, T-shirts, items of stationery and fifty-fifty duvet covers.

Yet, if we're honest, how much do most of usa really know about its creator, the Dutch printmaker MC Escher (1898-1972)? The truth is that outside his homeland Escher remains something of an enigma. Moreover, despite the popularity of his fastidious optical illusions, Escher continues to endure from snobbery within the realm of art, where his output is often denigrated as little more than than technically accomplished graphic blueprint.

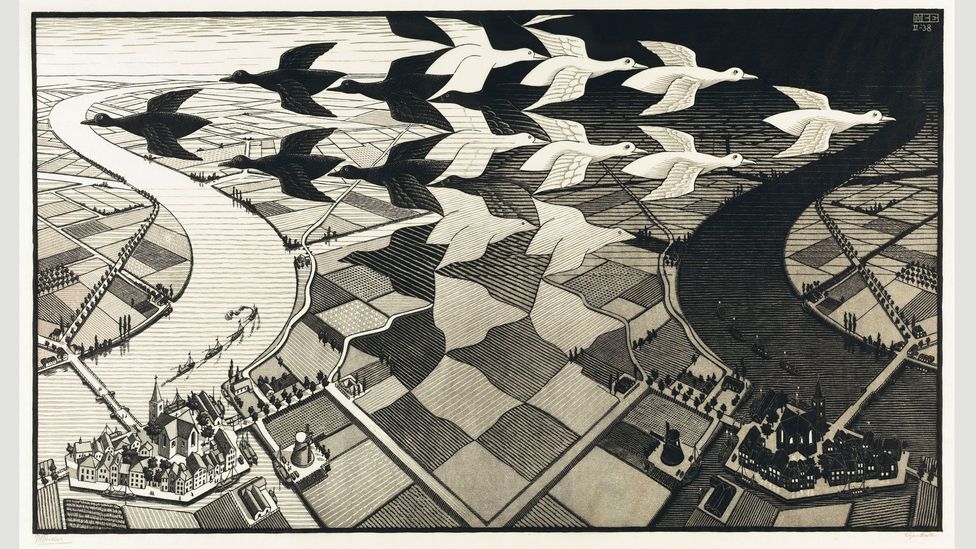

In Britain, for instance, it appears that merely a single work by Escher belongs to a public drove: the woodcut Day and Nighttime, which presents two flocks of birds, one black and i white, flight above a flat Dutch landscape in between a pair of rivers. Day and Dark was Escher's most popular print: during the grade of his lifetime, he fabricated more than 650 copies of it, painstakingly rendering each impression with the help of a small egg spoon made of bone.

Twenty-four hours and Nighttime was Escher's near popular impress: during the course of his lifetime (Credit: 2015 The One thousand.C. Escher Company – Baarn, The Netherlands)

Nonetheless, every bit Patrick Elliott of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Fine art points out, even the print of Day and Dark in the collection of the University of Glasgow's Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery "was actually acquired past the Geography Department and was transferred to the Museum at a afterward date".

So who was Escher – and does he deserve the indifferent reputation every bit a fine artist that fate has dealt him? These are some of the questions posed past The Astonishing World of MC Escher, a forthcoming exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, which also happens to exist the artist's get-go major UK retrospective.

'Miserable memories'

Born in the small urban center of Leeuwarden in the north of kingdom of the netherlands, Maurits Cornelis Escher, who was always known in his family as "Mauk", grew up in a prosperous household equally the fifth son of a civil engineer who was a senior official at the Department of Public Works.

At secondary schoolhouse in the city of Arnhem, where his family unit had moved in 1903, he had an unhappy time – and his miserable memories of this period of his life had a decisive influence upon many of his later prints, including Relativity.

Indeed, decades subsequently "the hell that was Arnhem", as Escher subsequently described his schooldays, he made a number of works featuring versions of the institution'due south dramatic staircase, which he had ascended and so often as a boy. The resemblance between the school's staircase in reality and the structures in Escher'due south prints is remarkable.

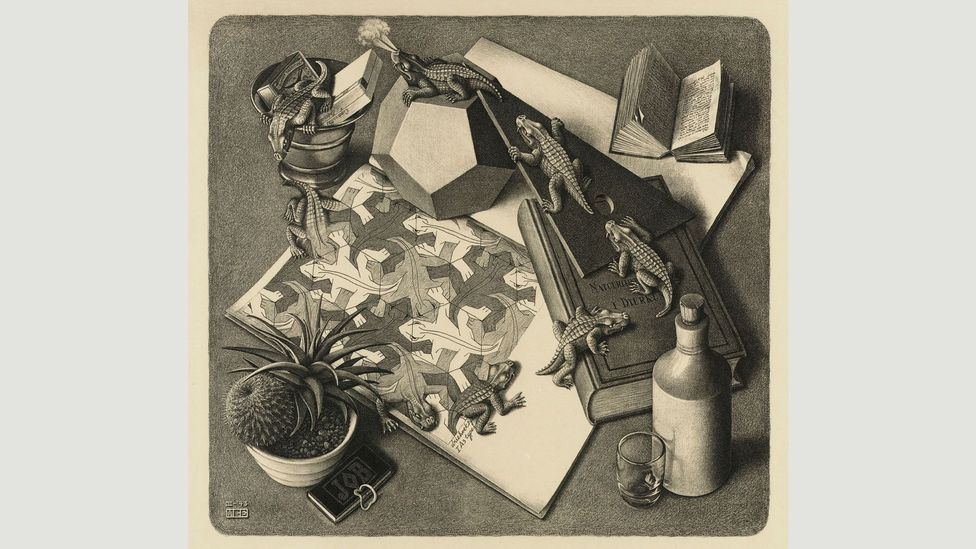

In 1919, Escher enrolled at the School of Architecture and Decorative Arts in Haarlem. His begetter hoped that he would become an architect, but, influenced by his graphic arts teacher, who had spotted his talent as a printmaker, Escher was determined to get an artist. Every bit an adult, he pursued this career – combining travel, when he sketched and came upwardly with ideas for future works (his two visits to the Moorish palace of the Alhambra in Granada were peculiarly important, since they taught him how to work with tessellating patterns), with long stints at home, where he led a remarkably orderly life.

"He had a severe daily routine mixing working and walking and coming together visitors," says Micky Piller, curator of Escher in Het Paleis, the museum devoted to the artist'south works in The Hague, where selections are shown from the collection of the Gemeentemuseum, which has also loaned works to the exhibition in Edinburgh. "He liked to detect nature, the sky, and birds. He loved classical music, especially Bach."

A 'one-human being fine art movement'

Despite his cocky-discipline, however, Escher only became able to support himself solely from fine art during his tardily fifties. By then he had discovered his master theme of perspective-mangling worlds, familiar from works such as Belvedere (1958), Ascending and Descending (1960), and Waterfall (1961), as well every bit Relativity. He was also known for executing his prints to a very high level.

Escher was known for executing his prints to a very loftier level, such as Scaffold Ascending and Descending (1960). (Credit: 2015 The G.C. Escher Company – Baarn, The Netherlands)

Occasionally, one gets the impression that this meticulous, sober man could be a lilliputian stuffy. During the '60s, Escher'south piece of work constitute mainstream popularity, as hippies delighted in its supposedly "psychedelic" qualities. (It used to be believed, incorrectly, that the plant at the centre of Balcony was cannabis.) Yet when Mick Jagger wrote to "Maurits" asking for permission to reproduce one of his pictures on the cover of the Rolling Stones' album Through the By Darkly, Escher refused, informing the rock star's banana: "Please tell Mr Jagger I am not Maurits to him." In 1965, Escher also turned down Stanley Kubrick's request for aid on a "fourth-dimensional film" (perhaps 2001: A Infinite Odyssey).

Still, this doesn't mean that Escher was humourless. "I like to think he was a rather placidity person, but very tongue in cheek," Piller says. "His relatives found him witty. He was open-minded and interested in the world and very dedicated to his fine art." Moreover, turning downward requests from famous people in other fields didn't cease his prints having a tremendous affect upon popular civilization. Some of his pictures did appear on anthology covers, including The Scaffold's L the P and Mott the Hoople's eponymous debut. They also became a reference signal for cartoonists.

Some of Escher's work appeared on anthology covers, including Mott the Hoople'south eponymous debut (Credit: 2015 The Thou.C. Escher Visitor – Baarn, The netherlands)

More recently, Escher's mind-bending visions have provided inspiration for the creators of The Simpsons, too as moving picture-makers including Jim Henson, whose 1986 film Labyrinth starring David Bowie includes a homage to Relativity, and Christopher Nolan, who created a dizzying, Escher-like dream sequence for his 2010 blockbuster Inception, in which the streets of Paris are seen to fold, buckle, and warp.

Jim Henson'due south 1986 film Labyrinth starring David Bowie includes a homage to Relativity (Credit: TriStar Pictures)

And then how should nosotros recollect of Escher – as a purveyor of visual conundrums and curiosities, or a "proper" printmaker working within a venerable tradition? He is sometimes called "a ane-man art movement", and this seems similar equally skillful a clarification as whatever, considering he didn't acquaintance himself with other tendencies in modern fine art, including the i – Surrealism – to which he was arguably closest in spirit. He also had few artistic successors: "Although he created something absolutely new," says Piller, "Escher has not directly influenced any artists."

At the same time, Escher was capable of concocting strong images with nigh-universal appeal – something, surely, to which almost fine artists would aspire. "At a time when abstract fine art was ruling the galleries," Piller says, "Escher fooled all of us by exploring such abstruse ideas as eternity, infinity, and the impossible in evidently realistic prints that were amazingly well fabricated. As the general public lost contact with the fine art earth, Escher's prints seemed simple and like shooting fish in a barrel to understand."

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else yous take seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

0 Response to "Mc Eschers Impact on Art What Did Mc Ehser Change About Art"

Post a Comment